In the world of woodworking, there’s a captivating technique that not only enhances the aesthetics of wood but also significantly boosts its durability. Shousugiban, an age-old method hailing from Japan, has gained global popularity in recent years. In this blog post, we’ll delve deeper into Shousugiban, why charring improves it, and how this technique combines water resistance and longevity.

Shousugiban: Rediscovering an Ancient Art

Shousugiban is a woodworking technique with its roots in ancient Japan. It was traditionally employed to make wood more resilient against the elements. The technique involves charring the surface of the wood, followed by careful brushing to remove the charred layer. What remains is wood that not only looks exquisite but is also remarkably resilient.

Sustainability and Shousugiban

In an era where sustainability is paramount, Shousugiban also shines as an eco-friendly choice. By enhancing the longevity of wood through charring, it reduces the need for frequent replacements and minimizes the demand for new timber resources. Additionally, the process itself requires minimal chemicals or additives, aligning with the principles of environmentally conscious practices. As the world seeks more sustainable building materials and techniques, Shousugiban emerges as a responsible choice that not only embodies the elegance of wood but also contributes to a greener, more sustainable future.

Enhanced Durability through Charring

Charring the wood is the key to the extraordinary durability that Shousugiban offers. By burning the outer layer, the wood is preserved and protected deep within. This process makes the wood resistant to insects, decay, and even fire. It’s astonishing to witness how what appears to be a fragile surface becomes an indestructible shield after charring.

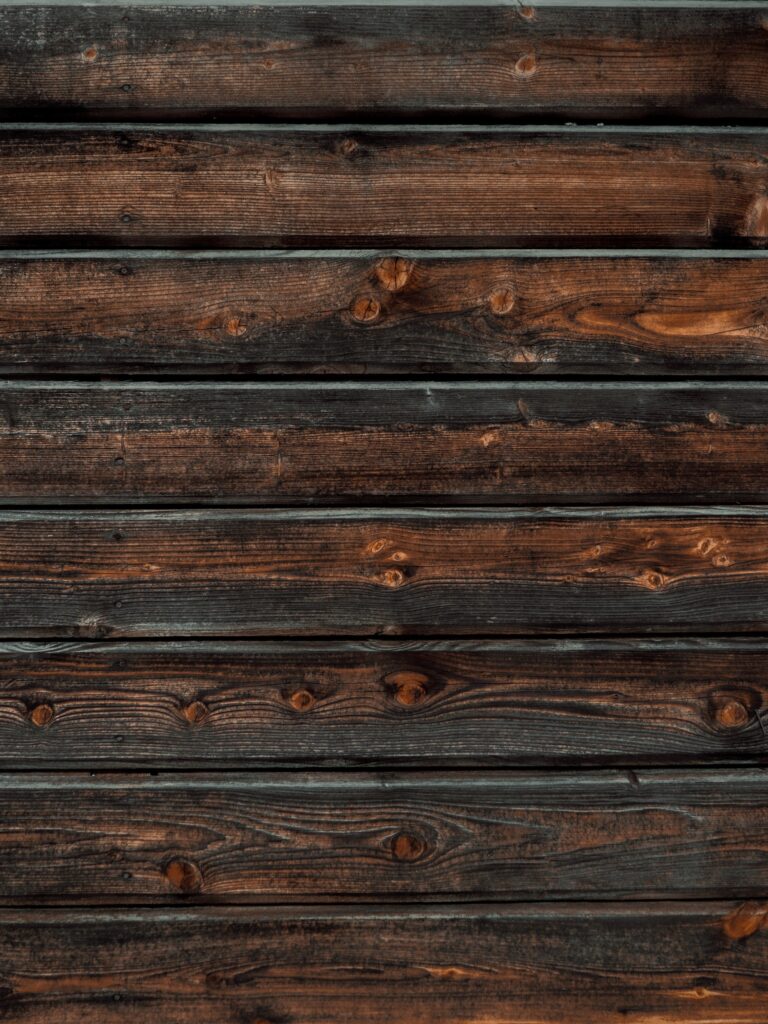

The Aesthetics of Shousugiban

Besides its durability, Shousugiban is also renowned for its aesthetic beauty. The charred surface imparts a unique texture and color to the wood, which can vary depending on the wood type and charring technique. This gives each project, whether it’s flooring, a facade, or furniture, a distinct elegance. The combination of strength and beauty makes Shousugiban a popular choice in modern architecture and interior design.

Water-Resistant and Long-Lasting

Another advantage of Shousugiban that shouldn’t be overlooked is its water resistance. Due to the charred surface, the wood becomes water-repellent, effectively warding off moisture and rain. This makes it an excellent choice for outdoor use, where wood typically faces significant wear and tear. Furthermore, Shousugiban is extremely durable and can last for decades with minimal quality degradation.

Innovative Applications

Beyond its traditional uses, Shousugiban has found innovative applications in contemporary design and architecture. From sleek exterior cladding on modern buildings to bespoke furniture pieces that exude sophistication, the versatility of Shousugiban knows no bounds. It has even ventured into artistic realms, with sculptors and craftsmen using the technique to create striking visual statements. This versatility showcases how Shousugiban not only preserves the integrity of wood but also allows it to adapt seamlessly to the ever-evolving world of design and craftsmanship. As designers and builders continue to push boundaries, Shousugiban stands as a testament to the enduring fusion of artistry and functionality.

Conclusion: Beauty and Strength in One

Shousugiban is undeniably one of the most fascinating woodworking techniques out there. The combination of aesthetic beauty, water resistance, and exceptional durability makes it an outstanding choice for various projects. Whether you’re renovating your home or crafting a new masterpiece, Shousugiban can help you achieve the desired blend of elegance and resilience. So, let this ancient art inspire you and explore the diverse possibilities of Shousugiban in modern woodworking.

Picture credit:

pexels – Gantas Vaičiulėnas